Carlos (dir. by Olivier Assayas) - Out of Competition

One of the key clues to understanding Olivier Assayas’ “Carlos” is right there in the soundtrack. Misidentified as punk rock by many reviewers, the throbbing rhythmic guitar tracks that play in the background throughout the film mostly come from the genre known as post-punk. Post-punk drew heavily from the sonic palette and methods of punk, but the spirit had been completely lost. Nihilistic though they may have been, punk rockers wanted a revolution - post-punkers just wanted to make music.

One of the key clues to understanding Olivier Assayas’ “Carlos” is right there in the soundtrack. Misidentified as punk rock by many reviewers, the throbbing rhythmic guitar tracks that play in the background throughout the film mostly come from the genre known as post-punk. Post-punk drew heavily from the sonic palette and methods of punk, but the spirit had been completely lost. Nihilistic though they may have been, punk rockers wanted a revolution - post-punkers just wanted to make music.

And so it is in Assayas’s 5.5-hour-epic “Carlos”, which functions not only as a biopic of internationally infamous terrorist Ilich Ramirez Sanchez, known popularly as Carlos the Jackal, but as a survey of the international failure of revolutionary Marxist guerillas during the last half of the 20th century – movements that started out as ideological above all else but descended into random violence that served no cause other than self-preservation.

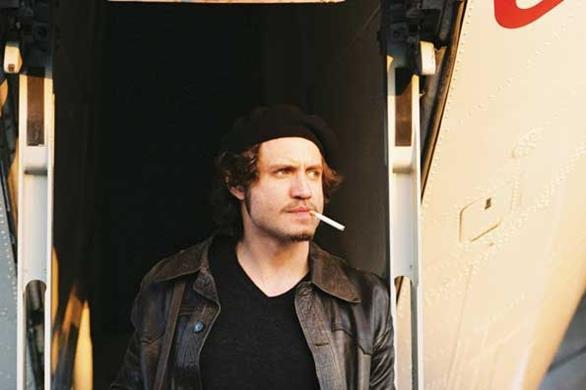

As portrayed by Assayas, Carlos, played by Edgar Ramirez, is a perfect harbinger of things to come. Carlos talks a good game – his only religion, he says repeatedly, is Marxism – but it’s clear that Assayas thinks he’s full of shit. Carlos’ concerns are far more local than global; if the spitting-image Che Guevara get-up he wears for a major hijacking operation doesn’t convince you of his all-consuming narcissism and need to be an icon, his first words to the hostages he takes certainly will. “My name is Carlos,” he says, smiling. “You may have heard of me.” And, of course, when the situation suddenly changes and he is forced to choose between the Church of Carlos and the Communist Manifesto, he acts in a way that would have Guevara gyrating in his grave.

It’s been a long time since I’ve seen a biopic that so thoroughly scourged its subject, and I’ve certainly never seen a movie that spent this much time doing it. “Carlos” seems like a reaction to movies like “The Baader-Meinhof Complex” (or for that matter, nearly any gangster film), which eventually get around to condemning their criminal protagonists, but not before admiring the thrilling way they live outside the law. You’ll be thrilled in “Carlos” as Assayas bounds from country to country, from criminal enterprise to enterprise. But you’ll be hard-pressed find anything admirable in this sleazily charismatic womanizer with frightening fetishes (Carlos quite literally makes his women handle his weapon), this self-aggrandizer willing to sell any cause he adopts out to the highest bidder, this dialectical materialist who couldn’t stop showing off his Mercedes.

“Carlos” was designed as a three-part TV series (which apparently kept it out of the competition, despite its superiority to most of the competing titles) and unlike the similarly long “Che”, where seeing both parts together was a must to appreciate the connections between the mirrored halves, “Carlos” would probably benefit from being watched in multiple sittings. In something of a rarity for trilogies, the second part is actually the most accomplished. The first and third parts, which are devoted respectively to Carlos’ rise and fall as his associations with various terrorist networks and governments change, have a relatively standard biopic structure, although Assayas ensures they always remain far from conventional.

The second part, on the other hand, spends over an hour on a single riveting set-piece before moving to other material, Carlos’ kidnapping of the board of OPEC ministers and subsequent escape attempt. Unrelentingly taut, the sequence is also notable for the way its extended length allows for the depiction of minute detail that is always revealing – the way Carlos engages the politician captives in conversation as equals, the way the politicians mold Carlos through flattery, the way Carlos’ subordinates pace and puke to manage their nerves.

For my money, Assayas is second only to Arnaud Desplechin as the most interesting director working in France today and his achievement in making this behemoth feel relatively fleet is stunning. Even more impressive is his decision to emphasize character over incident throughout the film. “Carlos” is no laundry-list of happenings. It’s a detailed depiction of a world of Carlos and his co-conspirators, all of whom are fully realized individuals, from the German terrorist disgusted with the anti-Semitism of Palestinian collaborators to the devoted feminist who is helplessly molded into a petit-bourgeois housewife by the charisma of Carlos. For all the sturm and drang found in this sweeping story, “Carlos” is a film about people who are venal, flawed, and above all, human, and that’s why this epic sticks in the mind.

-Raj Ranade

No comments:

Post a Comment